Panel Report: The Pandemic Pivot

- Eva Radke

- Apr 9, 2021

- 34 min read

Updated: Apr 12, 2021

Takeaways

Community-based, ad hoc responses mirrored New York City responses in terms of addressing PPE fabrication and food insecurity. Pro bono, local response reaches recipients in need sooner, albeit on a smaller scale, but nonetheless necessary until municipal relief arrives.

The City of New York recognizes that the film industry played an important role in emergency response throughout the years. The Office of Emergency Management is writing the playbook for the next administration to streamline potential public-private partnerships, including with the film industry.

Across the board, panelists agree that the film industry is a training ground for improvised problem-solving and ad hoc infrastructure development.

Staggered re-opening phases opened upstate New York to more production companies and needed revenue.

California's summer of rising COVID cases and historic wildfires boosted revenues for some of New York's production vendors.

Savvy business owners are not waiting for "things to get back to normal", they clearly see that COVID-era methodologies will morph into hybrid models.

Business owners with a deep and understanding and empathy of the clients' needs in a changing market, can lead to new enterprises, services, and products and builds a loyal client base.

Quick Links

Speakers:

Marielle Segarra, Adam Richlin, Andrew Stern + Patrick Rousseau, Debby Goedeke, Jason Weindruch, Jake Baer, Peter Hatch

Topics:

Response // Pro Bono PPE fabrication + Food Insecurity Relief

Retooling // Virtual Meetings + Hotel to Qualified Production Facility

Entrepreneurship // New Services and Products + Digital Marketplace for Prop Rentals

Peter Hatch: What the film industry can do now to prepare for the next crisis.

Included are action items you and your business can take now to work direct;y and indirectly with the City

Disease and the environment, prevention is less expensive than the cure.

Speaker Contact Information

From ad hoc supply chains, hybrid business model adaption, and COVID-era startups, the film industry remains quick to respond, resilient, and able to foster new ideas for the shifting business landscape.

March 2021 marked the first anniversary of the shutdown of New York. We dedicated our panel to those who rose to the occasion in adversity to create relief efforts and opportunities.

Response

The film industry vendors and freelancers who volunteered to address food insecurity and PPE fabrication via ad hoc operations were the stopgaps for a city and industry crisis. At the time, we did not stop to consider that our efforts were a pro bono indirect partnership with the City, but in hindsight, that's exactly what it was.

Here are just a few stories of the many pop-up relief efforts where the film industry's competencies and core values met at the crossroads to address a crisis.

Pro Bono PPE Fabrication

VIDEO: Dr. Ted Segarra of Downstate Hospital on ArtCube Army's PPE relief and what it meant to healthcare providers in the early days of the COVID-19.

Marielle Segarra,

Journalist, Citizen Healthcare Crisis Coordinator

Eva:

That was your brother in the video. And you are one of many, many of the requests that came to ArtCube Army from family members terrified for their caregiver loved ones. You're a civilian with no real ties to the film industry, then fortuitously hitched wagons with the with us in relief efforts, can you tell us your story?

Marielle:

I looked back at the initial email that I sent, which was March 27th, 2020. My brother had called me the night before. All this happened so quickly and the medical staff was really scared and the conditions at the hospital were awful at the time. They were trying to build out a lot of ICU rooms really quickly, and they just didn't have the supplies they needed. So for instance, in the ICU they had patient beds,

separated from the doctors' and nurses' stations by only a thin layer of cloudy plastic that didn't reach the floor. The fact that it's cloudy matters because the doctors and nurses couldn't see through it, so they couldn't monitor patient machines without actually going into the isolation area. And that means they have to use more PPE.

The patient room was open, the window was open, so the air was blowing directly from where the patients were onto the doctors and nurses who were stationed right there. And in some cases, they sleep overnight, and during their overnight shifts at the hospital were right around the corner from some of those patient rooms.

They didn't have basic supplies like masks and gowns and face shields.

They had some. But they were being told to take home their masks in a paper bag for a week, and just keep reusing the same one.

I think that happened at a lot of different hospitals.

So Ted called and asked for help. I think he just felt pretty desperate. I'm not really sure why he asked me because I'm a journalist. I don't have anything to do with this field, but he needed things like clear vinyl sheeting (aka marine vinyl) that would actually reach the floor so that they could monitor patients from outside. IV drip extenders so that we can put drugs to patients from further away again without having to enter patient areas."

So I put out an email to a community of radio and audio professionals, and I asked if people had any suggestions on where to get these kinds of supplies; it was kind of shot in the dark. A friend of mine put me in touch with her sister, Sally, who put me in touch with ArtCube Army and I didn't even really know much about what you were doing, except that you were making some supplies. And the outline of it wasn't entirely clear to me, but...

...it seemed like magic. Like you guys were able to source a lot of this stuff.

I think we raised a significant amount and started sending those supplies to not just downstate, but 149 other hospitals.

Downstate got a large portion of it. I know it meant a lot to my brother and his colleagues. Two of my brother's colleagues got COVID and died right around that time, in the spring, and it has had an enormous impact on them. They had to worry about themselves and their loved ones and whether they were going to die there to see what happened to their colleagues. And then meanwhile, they didn't know much about this virus or how to treat it.

So they were seeing their patients die despite everything that we're doing. Uh, and I think having this kind of support from the community meant a lot to them, it showed them that someone cared or that a lot of people cared. It's always hard to quantify, did someone not get sick because of the things that we did? But, I think that that almost certainly has to be the case.

Eva:

Were you surprised that the film industry was able to do this? When the world opens up again and we're shooting on your block and take up all the parking will you be just as annoyed? What are your feelings now that you have a little idea about what we're capable of?

Mariella:

Yeah, I thought it was amazing. I never thought about how when films are made, or about how all of the props and sets get there, who makes all that happen? I've learned about some shows like Saturday Night Live skits are written just a couple of days before. It reminds me of the news business because everything happens so quickly.

I think that's a superpower that you all have. I guess I've heard this kind of joke in several iterations, but if the film needs, like a giant shark by tomorrow, you figure out where to get the giant shark. The fact that you can do that for disaster relief, I think that is really important to know, because who knows what the next disaster is going to be.

The ability to pivot so quickly, just being able to fly the plane while you're building it, when you're not going to have an answer to right away, is critical.

And in those moments, it sounds like that's something that film industry production folks are really good at.

Am I going to get annoyed when you all the parking spots? Probably still yes. But whenever I saw it in Midtown, where I worked, I was always pretty excited to see what the program actually was. It was usually something I've never heard of or a dog food commercial or something.

Eva:

As founder of ArtCube Nation, a digital community of 1000's of New York City Art Department freelance crew and small businesses, our pro bono PPE fabrication happened via volunteer businesses and freelancers that have materials and tools on hand due to on-the-fly prop-making requirements. Thankfully, a lot of film fabrication businesses were awarded City contracts to fabricate very large quantities of PPE and hired prop makers to assemble face shields, a welcome paycheck in a bleak employment landscape at the time.

The gap in time, 42 days in this case, from signing a contract to mass distribution of finished goods, still left frontline workers vulnerable to viral exposure. In that length of time, determined, small, ad hoc operations emerged to bridge that gap until the local supply chain caught up. Businesses kept employees on the payroll, despite no incoming revenue, because our city's care providers needed us as we need them.

It was harrowing. Small businesses and freelancers risked exposure in the process but the pleas of overwhelmed healthcare providers and their terrified family members asking for help drove us to push forward. Rightly so, as historically, health providers are the first to perish in pandemics, and to date, more than 3,600 healthcare workers have died due to COVID-19.

We came together a year ago, and today, with work protocols and COVID compliance officers in place, these businesses are experiencing a return to business as usual to a lesser degree. When asked to speak about the experience, the common reply was, "I'm too busy. I'm making up for lost time and lost funding." One frankly said, "I just don't want to talk about it."

This video was created in April 2020, by BRIC TV mid-way through of efforts, tell the tale.

BRIC Arts Media, April 2020

Pro Bono Food Insecurity Relief

With freelance paychecks coming to an abrupt halt in the historically "slow" winter period in New York, pandemic food insecurity became a real problem for many freelancers who were not qualified for unemployment insurance, or if they were, NYC living expenses far exceeded what the assistance provided.

That's where Adam Richlan of Lightbulb Grip and Electric came in. At first, he offered his space to Feed the Freelancers and soon fell into being an integral part of the effort with the founder, Isabella Olaguera.

Adam Richlin

Managing Partner, Lightbulb Grip and Electric

Eva:

Describe the days between day one of realizing that grip and electric rentals were on hold and your first delivery of groceries to our community.

Adam:

I would say we were gearing up in the first half of March for a great spring. We had a lot of orders that were scheduled on the books. And then between March 13th and 16th or so I just watched everything cancel.

Over a hundred jobs canceled in four days, and it was just a flurry of cancellations. The state was about to shut down. I went from thinking was just gonna be another SARS-like thing passing through the country to "Uh oh. This is gonna shut us down for a while."

So we had probably a week or two of quiet. And then a friend of mine, Isabella Oliveira, this is actually her idea. She came to me and said, "Hey, we're doing this thing where we're collecting donations and we're going to go buy some stuff at Costco and make food boxes and give them out. Can I just use some floor space from you guys?"

Our checkout floor was doing nothing. And so I agreed. I sat on the side and let them do their thing. At one point, I was having a conversation with her because I enjoy logistics and processes and figuring out how to make things work better. I said, "Well if we put all the tables in a line if we could get someone to donate the boxes if we could find a better food supplier..." I always remember her comment was, "Well, you keep saying WE, so you're in on this?"

And so that became the start of me being the New York City flagship site leader for Feed the Freelancers. Then we partnered up with Red Hook Terminal who had a lot of food coming in their massive shipping terminal in Brooklyn, that there were a lot of huge shipping container ships already on the water moving food or fresh produce and stuff over from other countries that once the city had shut down, the restaurants had closed. There was no place for those two to go. They're just sitting on the dock.

And so we started. We got a call from them asking if we were interested in taking some food, so that started to change for us between, buying stuff retail and finding, you know, better avenues worked with Amy, who runs a service Rock Can Roll that helps catering companies and film sets repurpose unused food and gets it to charities.

So, with Red Hook, a story was that when we first when they first called, they had shipping containers of pineapples that they were not using and asked us if we would like any. We were doing about 100 boxes a week at that point, so we said, "Sure, we'll take 100 pineapples."

And when they delivered, it was an 18 wheeler, and they delivered us 48 ft tall pallets of pineapple because they shipped us 100 cases of pineapple. They don't work in single numbers.

In case anyone's wondering, you can fit 94 pineapples in a standard like film-equipment hamper.

Because we had all of those hampers from all those pineapples from our loading dock, we started getting more selective about our questioning. But we were getting everything from them from squash to fruit. All different. We got corn, we got whatever was in the shipping containers, they would just say, like, "Okay, it's fair game you have out to come by and come pick it up."

We started mostly to serve freelancers that weren't getting covered by any other government support service at the time.

Most freelancers don't have access to unemployment. Most freelancers don't have access to really strong support networks because we're all just this web of other freelancers, and nobody had anything to really grab onto.

We saw a lot of food insecurity, and we also saw a lot of people being unwilling in the film community to stand up and say that they needed help. A big part of being a freelancer is putting out this aura of they are always working. People were not as willing to share their hardships. We're trying to make it a little easier for them.

We figured out how to make it as efficient as possible. We were packing about 125 boxes a week. Every box gets a little label in the corner. And we had all of the boxes bar-coded and labeled for destinations. We got donated cargo vans every week for us to send out all the deliveries direct to doorsteps versus asking people to take the subway to come to meet us. We thought that was a safer option.

We really tried to think through, making sure that all of the boxes were

diverse foods that were nutritionally sound they could use in a lot of different ways if you come from a Spanish or Italian household, for instance. They could use these basic staples like beans and rice and bread and stuff in different ways.

It took us a while to get all this together, but it was a lot of logistics work and figuring out how to solve one problem at a time. As Marielle was saying about filmmakers...

...we are really good at solving problems that we don't see the full end of. We just know that we need to get started and we will figure it out along the way.

I think that makes for a really great team because we brought together about 15 filmmakers. Every week our roles were changing and what we had to do and where we had to go. Plans changed and everyone would just go with it. So, that helped us get a lot more done in a short period of time.

If we had waited for for for somebody to build a process for us, this would have never happened.

We made about 1500 boxes in total, and we assume that each box served about 33 meals or two weeks of food. In total, I think that's about 33,000 meals.

And so we served about 2500 freelancers. Everyone could apply for a box every week. And we had over 5000 applications, and these people came. These names came from everywhere from film and TV freelancers and photographers. And then it started branching out as people shared the link.

This was from a pitch for getting people involved originally. But we made a big survey asking for some basic information and then people were passing this link around, and so we would start getting networks of people who were independent contractors, babysitters, and bartenders. We would see one person find it, and then we would see a whole bunch of other people come in that were in that same genre, and we didn't limit it to just film and TV people. If there were people that applied that needed food, we pretty much just produce boxes as quickly as we could and then just kept taking the next chunk of names on the list, routing them two different boroughs, and then sending them out. Each has its own label and instructions for the user as to how the boxes work.

We also realize that freelancers didn't always have the best experience with cooking. A lot of freelancers also work 12 hour days constantly and eat on film sets, so we included a lot of recipe cards and instructions, especially when some of the recipients were getting four or five pineapples in the box to try to help us get rid of 800 pineapples, like pina colada and pineapple upside-down cake and the like.

The recipe cards kept continuing in our team would throw in recipes and family recipes that we had for different things that you can make out of whatever was in the box that week. Okay, we've got squash this week and bell peppers. Okay, maybe we can make some sort of summer stir fry kind of thing.

Eva:

You started with no system whatsoever and morphed it into that intricate system that helped 1000's feed themselves... Unbelievable yet unsurprising. Thank you so much.

RETOOLING

Film and Television production opened up in phases with strict guidelines, and hesitant clients, crew, and talent. Small businesses adapted to these new restrictions to keep the workforce safe and employed by retooling existing operations creating a new hybrid of services.

Andrew Stern

Be Electric Studios

Eva:

Tell us about your business in 2019 and describe the steps you took to retool your business to offer new pandemic-era services?

Andrew:

I'm Andrew, the CEO of Be Electric studios and equipment rental company. We have ten stages located in Bushwick, Brooklyn. We provide stage space and equipment rentals to TV shows, music videos, commercials, productions of all shapes, sizes, and colors.

2019, for us, was a really big year. We doubled in size twice. We acquired the former Brooklyn Fireproof stages, and so that bumped us up into the Level One Certification for the New York Film Tax credit as a qualified production facility.

And at the same time, we had already started construction on our largest stage Studio Ten. It was a lot of the really difficult thing to manage. Not something I would have chosen to do all at the same time. But that's just kind of how things happened.

We doubled in size and had the first TV show in Studio Ten. They started in November of 2019. Basically, they went straight up until the pandemic. Luckily for them, they wrapped right before the pandemic hit. But, just like Adam said, we started seeing the same kind of cancellations. By February, we started hearing from clients that production lines in China were delayed they couldn't get their products, and they had to push their shoot back, things like that. But by March, they canceled left and right.

I remember our last production was crazy. We had crew members walking off, people didn't feel safe. We determined we had to call it and we shut down. The governor's order for the shutdown came in a few days later.

Eva:

So what was your pivot?

Andrew:

We had a bunch more time on our hands. So we started reaching out to our clients and just kind of checking in and seeing how they were doing and what they're up to.

Everyone had the same question, "How do we produce content?"

We were all confined to our homes and so we could all get on virtual calls, and but we needed to raise production values and communicate with our audience in a more effective manner. We had already been doing live streaming events for a bunch of years and it just kind of made sense for us to move into that space in a real way. I'll turn to Patrick Rousseau to explain.

Patrick:

I'm Executive Producer of Be Electric. I've been producing live content and post-produced content, but live specifically for a little over a decade now. As you can see here live production pre-pandemic would look like this:

The directors, actors, clients, legal team, customer team, and social media teams were all sitting side by side. We knew that this was not going to be able to happen anymore, or at least for a while. And we started talking about what we could offer in the meantime that looks more like this:

We've all been on a million Zoom calls over the past year, but you can add graphics and brand colors, and of that kind of thing.

I worked on figuring out solutions to essentially what the television news world calls REMI, like on the news when they cut to a person on a satellite link to the main studio where your actual news host was.

We had to figure out replacements for that sort of setup so that we could bring people into our switchers remotely, but still have the ability to design the screens, adding lower thirds cut to pre-recorded content in a really seamless way.

Our clients demanded polish, so we tested out a bunch of different solutions and figured out some best practices for a couple of different budget levels using different

tools, depending on how many people and budget for the project. Everything from, elevated Skype calls to a blend later on in the pandemic.

By the summer, when things were seeming a little safer and we could open up the studio so we could do hybrid events where we have one person in the studio interviewing remote guests from all over the world.

We produced hundreds, if not thousands of hours of content for companies big and small.

I could be sitting in my basement with two computers with a desktop, two screens, a laptop, and an iPad, controlling the seamless Zoom call.

Eva:

Wow. A polished, seamless Zoom call! Any organization could use your service, even for this Zoom Webinar right now, that would be fantastic to have an experienced producer backing up the speakers. Thank you!

Debby Goedeke,

Albany County Film Commissioner

Eva:

Shutdown phases were lifted earlier upstate, and that opened up more production opportunities for upstate New York. What did you do to retool Albany County to keep the cameras rolling, crew and talent safe, and production spending in New York State?

Debby:

Like everybody else, we were in a survival mode in the beginning, and then we started following the governor's restrictions as they lifted concerning media production.

So, we knew we would need to continually update our website, utilize social media more often, announce what phase we were in, provide links to production guidelines from the CDC, post where New York State Health Department Health COVID testing sites opened, and the list goes on. We really wanted to focus on everyone's safety when they were here. That was a top priority for Film Albany, not only for the productions but for our community as well.

So we started to share those real-time examples. Amazon came with Modern Love. They filmed eight weeks in Albany. They were safe. It was a huge success, so we wanted to get that message out.

We also knew that updating our website consistently was working because our Google analytics reflected that our Film Albany website hits were quadrupling.

We also knew we had to get creative not just with the qualified production facilities that we had, but we explored how else could we keep everybody contained when they came here for film production. I actually heard a producer on a webinar talk about film offices thinking "outside of the box" And what venues could double as a qualified

production facilities, but keep it all contained.

So I immediately thought of our top four hotels that have ballrooms and the square footage that would meet the qualified production facility criteria. So the Hilton in downtown Albany reached out and they wanted to work with us.

But we also needed to have a conversation about film production. I explained that it isn't a meeting or a convention. It's not a supporting sporting tournament. This is a whole different animal.

The hotel would need to be, COVID-health-conscious, expecting late nights, early mornings, special catering requests, parking, security, and flexibility. We all know what's involved. My thinking was to build an interior set in the ballroom and use the surrounding breakout rooms as production offices. In addition, that hotel has over 300 sleeping rooms and suites, so they really could keep everyone contained if they needed to.

Of course, our hotels were suffering and are still suffering, so that would bring much-needed revenue. The hotel was completely on board. We filed the paperwork with the governor's film office, and they're now a well-qualified production facility.

There's been a lot of inquiries about it. No one's taking advantage of it, but you know that doesn't bother me in any way, shape, or form. It shows that we're thinking of ways to take care of our clients that might not necessarily be what the normal is.

Eva:

Thinking outside the box is also essential for entrepreneurs so they are unafraid of big ideas, rolls of the dice, and nimble solution-oriented operations. Thank you, Deb, given your experience and nimble thinking you retooled a hotel into an opportunity.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Start-Up Nation cites vision, tenacity, confidence, financial prudence, work ethic, and resilience as some common characteristics of entrepreneurs. There is an ongoing/ never-ending debate if entrepreneurship is an innate quality or if the skills can be learned or adopted. Start-up circles commonly cite is the difference between CEO and entrepreneurs as sometimes, the two are like oil and water.

Entrepreneurs tend to have skills focused on coming up with new ideas, pitching to investors, and building a business infrastructure with limited resources. CEOs' skills focus on maintaining and growing a business once it’s already been established, and typically less adaptable with lower risk tolerance than driven, visionary entrepreneurs. Forbes lists high fluid intelligence, high openness, and moderate agreeableness as gauges to predict a long-term successful start-up operation.

The following panelists illustrate how the characteristics required for a successful business are not limited to a first-time or long-time CEO or founder, but an intimate knowledge of their market, empathy for the client, and desire to build solutions, not just revenue. A CEO can most certainly be an entrepreneur, but the blend seems to hinge on the desired outcome informed by knowing and empathizing with the people who make up the "market".

Jason Weindruch,

co-founder of Street Team Studios

Eva:

You're two years into a brand new business, a startup that sells and rents production supplies, expendables, and walkie-talkies to productions. What was your Pandemic Pivot and what entrepreneurial skills did you employ to introduce options from your operation?

Jason:

First off, I just wanted to say with humility, I feel a little guilty as an entrepreneur finding success in the pandemic that hurt so many small businesses that continue to suffer. So I just want to say that right upfront.

It was our goal to be solutions-oriented, and we felt that adaptability and attitude which we call the Two A's, were going to be the two most important things that we could embrace in response to this pandemic.

We knew there was going to be big changes, and we didn't want to be a Blockbuster Video. Blockbuster was offered many opportunities to adapt and enter the streaming business and they dug their heels and said 'no'. We all know what happened to Blockbuster Video.

We wanted to avoid the "waiting for things to go back to normal" attitude.

We were closed from March 23rd to May 29th, but we ended up working during that period. We got up, we showered and we started safely working at 9 a.m. every day, whether that was remotely or socially distanced. We made modifications to all of our existing products and services and implemented new policies. To this day, employees take their temperature and record it every single morning before they come to work. We have not let our guard down at all.

From the company's perspective, we haven't raised our prices, yet we're spending thousands of dollars to protect the employees and the customers.

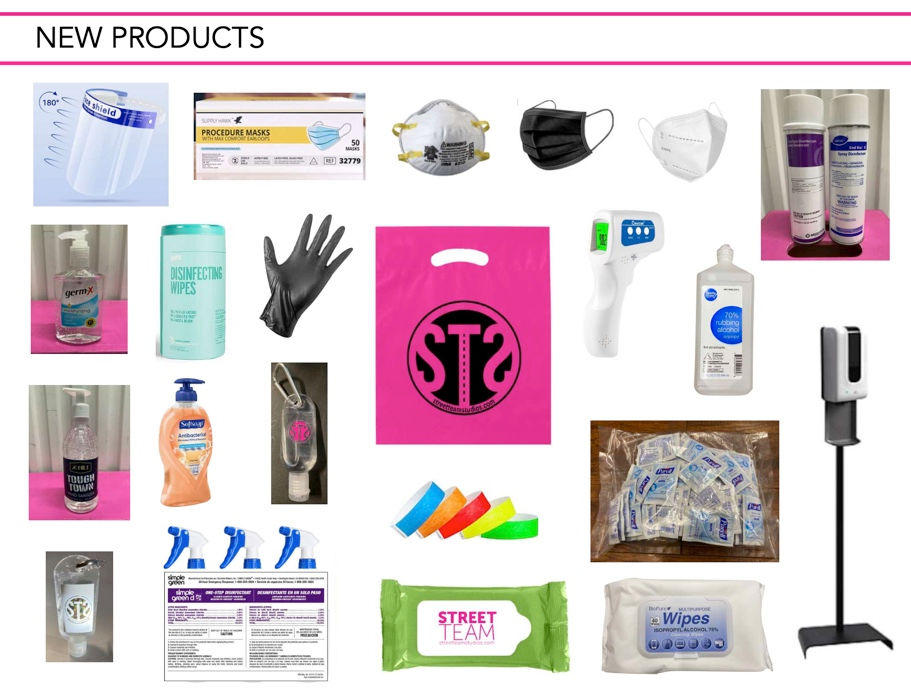

Here are some of the new products that we added - a smorgasbord of different things that we've added to our inventory.

These new products were six-figure expenditure that was completely unexpected having to adjust to this, to say it was nerve-racking is an understatement. With the amount of money that was going out trying to adapt, we came up with PPE kits, but our customers, you know, wanted modifications.

So we did. So here is a basic PPE kit that we came up with.

And as time went by, customers were asking for the two-ply or three-ply surgical masks, for a multiple-day shoot, they asked for bigger hand sanitizer gel,

The answer was always 'Yes'.

Some customers said they really liked our pink bags and asked if they could turn them into individual craft service bags so that we can dole these out to crew members instead of having them come to the table. We're selling these things like crazy just word-of-mouth.

We do offer disinfecting service, but not every budget can afford that. So we put together disinfecting kits so that production teams and COVID coordinators could pick up a kit for themselves, do it themselves. We tried to make everything scalable for different budgets and different projects.

This is the Disinfecting Kit, it literally became my full-time job to be a buyer. The whole role has changed for me for six months. All I did was try and source, PPE and disinfectant and different things.

.

I really think that my background as a producer and production manager, put me in a unique position because a lot of folks in production are really great problem-solving.

Somebody mentioned earlier about getting a shark the next day. You know, I've been in that position where someone one set said, "Hey, we need a reindeer tomorrow." So I think that my background put me in a position where I can help the production community source.

Regarding the disinfecting service, these are the different machines.

There was a lot of price gouging going on at the time for machines like this. So we were paying two and three times the market value for them, but we thought it was important to get them for the community.

To date, we have disinfected countless film locations, yoga studios, Olympic size swimming pool houses, apartments, stages, studios, vehicles, restaurants, bars, cafes, churches, schools, gyms, production offices.

Dan is actually disinfecting guitars for Paul McCartney, who was out in the Hamptons and on the right, Colin is disinfecting the Parlay Studios in New Jersey. Basically, when the crew went to lunch, he suited up and disinfected the entire stage.

We also made a lot of modifications to our existing inventory. We have a lot of fashion clients for Fashion Week, and we had to make some changes to socially distant our popular hair and makeup mirrors.

I mentioned the crafty bags, which are on the secret menu, but crafty baskets have become wildly popular. We could never imagine the success we're having with these. They sell out every single week. We know that the days of chip bowls and tongs were over.

We also added beverages so that Production Assistants (PA) had fewer stops to make. The fewer stops the PAs make, the lower the chance that they can introduce COVID to set. So it's really been our aim to eliminate as many stops as we can for the Production Assistant.

Interestingly enough, we had a giant surge in business the last half of the year because of California. It was a combination in L.A. and California experiencing COVID spikes and a historic fire season. So we saw an incredible spike in business in the last half of last year. Most all of the production companies that we saw had California addresses. So there was definitely an impact for us from California.

That was our experience. We leaned into the philosophies of the leaders that we respected. You know, Steve Jobs, Simon Sinek, Albert Einstein, Brene Brown, Mark Cuban. These are all people that we really look up to.

We doubled down on our core values.

We try to find the best product service and solution for our customers and provide great service. That's very much in line with Steve Jobs' thinking,

We had always been very careful about hiring employees, but it became very clear to us that hiring for attitude is so much more important than hiring for skills.

You know, the pandemic was definitely traumatic. We accepted there will be an ever-changing new normal and we would not wait for things to go back to "normal". That may be the most important thing.

Original ideas are a little bit overrated. During the time of brainstorming, we're trying to come up with all these novel new ways of thinking, but in reality, embracing a great idea that already exists and just doing it better or adapting it to our industry

for our customers ended up being the winning solution.

Eva:

That's fantastic. Before we get to Jake Baer, I want to address one thing. You said you felt a little guilty. It's really okay. when you're doing good, it's okay to do well at the same time. These accidental successes come out of your good heart, lateral thinking, and entrepreneurial spirit.

Jake Baer,

CEO 1RentPlace + Newel

Eva:

We just heard from a brand new start-up. On the other side of the coin, is Jake Baer, CEO of 1RentPlace and CEO of antiques giant Newel.

Since then, Jake took some cues from the expanding film industry then he founded 1RentPlace, a digital marketplace for rentable, luxury furniture set and home decor.

Jake, often entrepreneurship addresses pervasive issues. 1RentPlace addresses an expanding market in the rental space. Kindly lay out the details of the expansion of the market, how that happened, and the issues that you address with your technical solution?

Jake:

Well, that's those are all really great questions. I've been able to see the expansion in the market really within my own business at Newel. Just being in a situation where we took really a predominantly retail business about four or five years ago to a rentals business. I went through our entire inventory of 30,000 pieces. I put rental prices on items and I catered to the rental clients. I saw the opportunity written on the wall, just like the recent expansion.

Plus, I just love set decorators, it's a passion of mine. I just want to support them.

Now our rental side is bigger than our sales side. We just added an extra 10,000 more square feet for a total of 95,000 total. I speak to clients every single day, and I hear how frustrated they are sourcing quality inventory, it's kind of archaic in the center.

If you type something into Google, you get a bunch of links. I want to be in a spot where I could bring a lot of people who are struggling through Covid, and that's kind of how 1RentPlace started.

All these dealers came up to me asking how to start renting their inventory. They had no established outlet for it. It dawned on me that I could bring all the dealers all over the US and Canada to one platform, give them the storefront, and we'll market to the set decorators. We're really trying to build a community to support. We've signed on close to about 40 dealers so far.

It's a business community that is very scattered. There's just a lot of different moving parts, and if we can make it a safe environment, we'll do it. We're not looking to interfere with people's businesses and we're not taking a commission. We just want to be the spot for these incredible clients of ours to source from curated, small businesses that have exactly what their project requires. In turn, 1RentPlace provides a platform for them to add additional revenue streams, ensuring this web of vendors stays connected and in business, which is good for all the players.

Eva:

Sounds like you are doing just that - building a community and culture of collaborators, not competitors.

In 1939, the year that Newel was founded, was also the same year that Alan Turing, father of theoretical computer science, was worked as a code-breaker for the British Government.

What do you think your great-grandfather would say if you told them that in eighty-two years his antiques would soon be available to the market on a portable electronic device?

Jake:

I think he would be incredibly proud. He would probably tell me, "Jake, why don't you get more inventory?" I'm very proud my great grandfather started this. I've never met him, but I think about what he would do every single day. When I wake up, I ask myself, "What would he do today?"

We were the first Antique company to have a website. This is before 1stdibs.

Newel has always evolved with technology.

When the pandemic hit, we were in the exact same situation as a lot of other dealers and prop houses. We were growing, we were expanding, and then all the rentals stopped. We didn't have any money coming in. It was definitely scary. Thankfully, we have a sales side of our business. That's why a lot of businesses need to find alternative ways of making money and multiple revenue streams. That's why I thought of 1RentPlace.

We launched three weeks ago and it's really special to be being able to see the number of clients visiting the site. Orders starting to be placed, and it's very exciting to be a new marketing tool for contemporary, antique, and vintage dealers. Established rental companies can also join and add themselves to the amazing community to help the most talented people in the world get the job done.

Eva:

I think the power of community is a theme we're hearing today. Congratulations. I'm sure your great grandfather would be very proud of you.

Let's turn to Peter Hatch.

Peter Hatch

NYC COVID-19

Public-Private Partnership Czar

Eva:

Thank you so much for joining us. I realize what we did as an industry is a nano-cosom of what you had to do. You were named the COVID-19 Public-Private Partnership Czar. in March of 2020. Take us back.

What happened when you got the call to the appointment And what were your priorities and first calls?

Peter:

First, let me say thanks to you and the panelists and the whole industry that's represented here.

You know, the mayor, the administration, and I know how important this industry sector is to New York -- such a big employer, how hard hit it was.

But as I was preparing to join you today, I learned how many of my colleagues who worked in the COVID response over the last year were aware of various projects -- both contracted with the city and pro bono -- that players across the industry contributed to the response, like how fresh in their minds it was.

On behalf of everybody on the city side, let me just say thanks. It was powerful to hear those stories again today, but we remember them and look forward to working together, preparing for any future events.

So, in March of 2020, part of why I was appointed to this role was because it was clear at that point that there would be no well-coordinated federal response.

We were not going to see shipments of needed health care supplies, PPE, ventilators, et cetera, out of the federal strategic stockpile. The cavalry was not coming.

So New York City, given its scale, decided we would have to act ourselves like a state, which had largely been left to their own devices by the feds, or even like a nation-state. Our mayor committed the whole city, all its agencies, to the response. It was led, of course, by our public hospital system, NYC Health + Hospitals, and our Office of Emergency Management, but we put all agencies into play.

But even then we knew there would be a gap in time, a gap that many of my fellow Panelists spoke about, before, materials that we could procure would arrive, before before mutual aid from other states would get here.

So we realized the city government wouldn't be enough and that we would need public-private partnerships to provide fast and flexible resources that would fuel that response and help our municipal service delivery be bigger and faster.

So I was appointed to this role to kind of oversee that process.

Most critically, in March, we realized that we were not set up to ensure that we could successfully accept the outpouring of private assistance that was coming our way. So we set up a COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund at a city-affiliated nonprofit. We had to build a new web portal to take large-scale PPE donations, for example.

We also knew we were going to have to solicit types of support the city hadn't asked for before. We needed private building spaces for hospital beds, so we set up a portal where large real estate players like stadiums and hotels could offer to share their space. We had to learn how to procure not just out of our hospital system, but citywide, for items like PPE for which there were broken global supply chains. So we had to figure out how to buy both in the U. S., from middle-market players, and globally and then ship things here ourselves.

We had to learn to manufacture PPE in order to deliver the health care that was needed. We had to recruit healthcare workers. We had to build operations for all of those things.

Our focus in those early days was, of course, healthcare delivery as priority number one, then emergency food and supporting remote education for public school students, and, later on, emergency financial relief. We increased hospital capacity in the city by 26,000 beds. We recruited 14,000 healthcare workers from around the country, and we supported those workers with food, transportation, child care. As an example, we delivered 400,000 grocery bags to healthcare workers at 100 hospitals, and 200,000 meals to our public hospital systems, morgues, nursing homes, etcetera.

I know that there were local TV productions that were also doing meal delivery. Adam spoke earlier about gap filling for food-insecure community members from your sector before the city was able to set up the Get Food program, which ultimately scaled to doing more than a million meals a day with no eligibility requirements, that is, anybody could apply. But that wasn't up and running in early March. So thank you for filling those gaps in the early days.

And of course, we had to solve for PPE. So we built a citywide, not just hospital-based, procurement operation. We also were soliciting massive donations -- 10,000, 100,000 units -- from unlikely partners Goldman Sachs, Apple, Facebook, Peloton, and Louis Vuitton. We had Anheuser-Busch making hand sanitizer instead of beer for us.

We took donations in from the TV and film sector from Warner Brothers, Viacom, Disney, and local TV productions that used masks on set. We were taking in donations from The Metropolitan Museum that uses PPE for restoration efforts.

We also learned to make masks for items that weren't the public-facing, core business service but instead were for the industry’s other capabilities. So we were getting plastic for face shields from soda bottlers, and logistics, trucking, and warehouse support from department stores like Century 21 or chains like Starbucks. I think this is very relevant for how your industry can be useful, going forward.

It's not just about the product you're typically making or selling, but it's what you can do and all of the people who can do it.

Eva:

Those unlikely partnerships turned out to be really successful. In this effort, you and I know there are failures along the way. So when I ask the question, understand I know there is no winning, there is just losing as little as possible. The pandemic really hit New York really hard and early without the benefit of scientific research and sufficient PPE.

Between 9/11, Hurricane Sandy, and COVID, we've had a major disaster every 6.5 years. In hindsight what tweaks and permanent changes have New York City adopted to prepare for the next crisis?

Peter:

Thank you for that question. We are pleased with our partnership with the Biden administration now, it has added a massive shot in the arm, if you will, to our efforts here to fight back COVID. But we're going to assume that there's going to be no federal support. New York City will continue to orient itself like a nation-state.

We will assume that a future event may not be geographically concentrated the way 9/11 or Sandy was. It could again be a citywide impact that is not just economic but also hits physical health.

We've built our own strategic reserve rather than relying on the Feds. We have built abilities to do procurement in different ways. Hopefully, if there is a future event, it won't require procuring PPE, but it might. We've retooled the city's procurement operations to be more nimble in the case of an emergency.

So if there's some other sort of goods and services we need to get at mass scale, we'll be able to do it better. This was the first experiment in a long time in manufacturing our own products.

When we began thinking about not just how much can we buy or how much can we take in as donations, we understood we also could make face shields, isolation gowns, masks etcetera. We turned first to manufacturers in the Navy Yard, costumers and seamstresses were some of the early thinking. Knowing that film TV and Broadway were idled and all the skills were there, that's really where we began first, and you shared some of those stories where it was both owners and the unions coming together to offer space skills, materials, but also unusual partnerships.

One I recall was we had a fashion company that teamed up with a U. S. Military body armor manufacturer to make hundreds of thousands of isolation gowns at the Yard. Really, really critical. That's something we would want to maintain our capability to turn on again, if we needed, to make something different.

We will be able to leverage the city's incredibly large and diverse health care delivery system and life sciences sector for a future public health event in a way that's just much more integrated now and, maybe most importantly for this conversation,

The Office of Emergency Management right now is writing the playbook for the next administration, in response to the learnings from this event and are building on the need to anticipate having to be able to centrally coordinate public-private partnerships...

...as opposed to reinventing the wheel as we did in March of 2020. That's going to be built into the plan.

Eva:

Thank you, Peter, for joining us today. It is very meaningful you took the time to speak with us and we do look forward to partnering and planning for the future.

ADDENDUM

Sadly, we ran out of time, but Peter Hatch wanted to share with the community there are ways the film and TV industry support our city in ongoing and event-specific ways.

Government is best at delivering large-scale, uniform services via strict procurement rules to avoid corruption and liability and to ensure equity. That can make partnering with the government on an ad hoc, emergency basis a challenge. With that in mind, in the next event, there definitely are ways to aid New York City in times of crisis.

1. Direct Partnership with the City

A. Pro Bono

Stopgap operations until government aid arrives.

(e.g. Mobile generators, until government generators arrive.)

B. Contracted

(Rental of space, trucking, lighting, or manufacturing.)

Action Items:

Register your business for PassPort here.

PassPort (Procurement and Sourcing Solutions) makes it easier to complete and throw your hat in the ring for contracts and complete procurement tasks.

Register your M/WBE here.

For M/WBEs (Minority and Women-owned Business) interested in doing business with the city and its agencies.

C. Staffing

Volunteer, temporary, or permanent hires.

Action Item:

Vaccine for All Corps is hiring. Apply to work here.

The City is hiring 2,000 New Yorkers to work on City-run vaccination efforts as part of the Vaccine for All Corps.

No healthcare experience is required for many positions, which include roles in site management, operations, and client services, in addition to clinical roles.

2. Indirect Partnership with the City

Every film industry vendor and freelancer can fill the relief gaps at the local level via grassroots partnerships. Local governments paint in broad strokes that inadvertently miss nooks of the population. It's essential for the film industry to recognize we, too, have a role in relief in ongoing community support efforts and in times of crisis.

Leveraging your specializations and resources eases the strain on harder-hit New Yorkers. You are helping the City by helping others and you are helping others by helping the City, and in the end, you'll reap the benefits of a vibrant, healthier community.

Action Item: Adopt a mutual aid group in your neighborhood to volunteer and/or donate items often used on film sets to help them help others.

For example, North Brooklyn Mutual Aid provides hygiene kits to unhoused neighbors.

The film industry can and should donate new and unused partials of common production supplies or set dressing that too often ends up in the waste bin!

Moderator Final Thoughts

Climate change and disease prevention are connected. Prevention is less expensive than the cure. Let's not wait for the next crisis, but prevent it.

The cost of preventing the next pandemic is 2% of the cost we’re paying for COVID-19.

Six out of every ten infectious diseases in people are zoonotic, which makes it crucial that we strengthen capabilities to prevent and respond to these diseases using a One Health approach. This recognizes the connection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment and calls for experts in human, animal, and environmental health to work together to achieve the best health outcomes for all. Source: CDC

A study published in Science, “Ecology and Economics for Pandemic Prevention,” found that the costs of preventing future zoonotic outbreaks like COVID-19—by preventing deforestation and regulating the wildlife trade—are as little as $22 billion.

The economic and mortality costs of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic could reach $10-20 trillion, some economists predict.

As an industry, preventing the next pandemic or climate change event partly lies in all of us re-examining the impact our businesses have on the environment, which contributes to the proliferation of disease the more contact humans have with animals.

Imagine if all business owners had the choice to either invest 2% of the revenue lost in 2020 into their business for waste reduction, retro-fitting, or sourcing sustainable materials or do nothing and let the pandemic ride. We wager they would choose the former.

So, as your business recovers, now is the time to retool operations, procedures and priorities. Every sustainable choice, purchase, or retrofit makes a difference.

Where to start? Reduce carbon emissions from transportation, set construction and landfills.

Transportation/Energy

95% of the world's transportation energy comes from petroleum-based fuels, largely gasoline and diesel. Fossil fuel use is the primary source of CO2, a greenhouse gas. Source: EPA

Retrofitting and Solar Power

Retrofitting offers fleets several benefits, including:

Lower greenhouse gas emissions

Reduced operating costs

Extended vehicle and equipment life

Reduced spending for new vehicles and equipment

Visit Green Fleet for more retro-fitting information.

Solar-powered generators and vehicles have similar benefits

Reduced noise and fumes

Fewer fuel spills and malfunctions

Lower greenhouse gas emissions

Alternatives exist! Speak with the good folks at Shattered Prism or Quixote Studios about the benefits of their future-friendly generators and production vehicles.

Deforestation

Set Fabrication

Deforestation not only allows the diseases that transfer from animals to humans more easily but reduces the ability of the forests to absorb CO2.

Source FSC certified wood

Rent set elements or source/donate reusable standard sizes flats.

Alternatives exist! Thankfully, the leading lumber supplier to the film business, LeNoble Lumber. has one of the largest sustainable building supply selections.

You can find free (!) or reduced-price set elements on ArtCube Nation directly from another production.

ReadySet has ready-to-shoot walls, floors, shapes, and surfaces.

Landfill Emissions

Landfill gas (LFG) is a natural byproduct of the decomposition of organic material in landfills. LFG is composed of roughly 50 percent methane, 50 percent carbon dioxide (CO2) and a small amount of non-methane organic compounds. Source: EPA

Donate reusable items to one of the 153 donation sites. Dumpsters full of new, reusable furniture, office supplies, wardrobe, and raw materials not only rob shelters and mutual aid organizations from the benefit, but the items are also destined to generate landfill gas needlessly.

Hire a company to do it for you. Earth Angel is an NYC-based sustainable film industry service with a business model that provides trained staff, sourcing and data analysis.

Offer a free "Wrap the Wrapper" service. Partner with companies like TerraCylce. When they return the rentals, they can also bring back hard-to-recycle packaging, bubble wrap, and packing peanuts that usually go straight to the landfill.

“Being a good human being is good business.”

Paul Hawken, environmentalist, entrepreneur, and writer

CONTACT INFORMATION:

Andrew Stern

andrew@beelectric.tv

718.484.1466

Adam Richlin adam@lightbulbgrip.com

Jason Weindruch

streetteamstudios@gmail.com

917.790.3100

Debby Goedeke

Eva Radke

eva@artcubenation.com

Comments